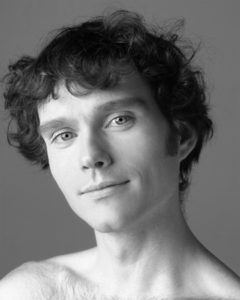

At age nine, Jeremy Nasmith joined St. Simon’s Choir, which was directed by Dr. Derek Holman. He also began to study ballet with Marshall Pynkoski and Jeannette Zingg, who founded Opera Atelier the following year. He toured with St. Simon’s Choir to Norridge Cathedral and Westminster Abbey in England, and performed in numerous performances with Opera Atelier. From the age of 15 until he finished high-school, Jeremy concentrated on ballet and toured as a dancer with Opera Atelier. After high school, he also trained with the National Ballet of Canada and joined the company when he was nineteen. He danced for many years with the National Ballet of Canada, but later left the company to become a free lance dancer. Jeremy now tours the world dancing with companies in Japan, Korea, Europe, the United States and Canada. He is also a choreographer and a composer.

At age nine, Jeremy Nasmith joined St. Simon’s Choir, which was directed by Dr. Derek Holman. He also began to study ballet with Marshall Pynkoski and Jeannette Zingg, who founded Opera Atelier the following year. He toured with St. Simon’s Choir to Norridge Cathedral and Westminster Abbey in England, and performed in numerous performances with Opera Atelier. From the age of 15 until he finished high-school, Jeremy concentrated on ballet and toured as a dancer with Opera Atelier. After high school, he also trained with the National Ballet of Canada and joined the company when he was nineteen. He danced for many years with the National Ballet of Canada, but later left the company to become a free lance dancer. Jeremy now tours the world dancing with companies in Japan, Korea, Europe, the United States and Canada. He is also a choreographer and a composer.

Q. You sang professionally at a very early age. Has that training helped your dancing?

Absolutely. Music is the time in which the dance exists, so to understand music is to understand how to move to music. To sing a phrase of music one must choose which notes to accent or shade and how much breath is necessary to complete the phrase. The same applies to dance: an enchainment is a phrase of steps which must be accented or shaded in correspondence to the music, so any musical training will help a dancer to inform their performance, as my vocal training helped me.

Q. You trained and danced with Opera Atelier, a company that specializes in early music opera productions. Is the training for that kind of dance very different than what dancers study for classical ballet?

I don’t know if there exists a specific method of training or syllabus for baroque dance. In my case, I studied classical ballet (R.A.D. syllabus) with my teacher Jeannette Zingg, and learned baroque dance during rehearsals for the various productions we were doing. But because classical ballet grew out of baroque dance, many of the steps are the same, or extensions of the same, so once you’ve learned the classical ballet vocabulary it’s easy to make the switch to baroque dance.

Q. While in high school, you toured Europe with Opera Atelier. Was there anyone else your age? Was it during the summer? What kind of provisions were made for you? What was touring like for you?

That’s right. Opera Atelier toured several destinations in Europe with a double bill production of Jeremiah Clarke’s ,i>Ode on the Death of Henry Purcell and Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. I was in grade 12 at the time (18 years old) and was the second youngest person on the tour (the youngest being Khatu Le, another Opera Atelier trained dancer, since retired from dance.) The tour took place during the school year, so I was responsible for continuing my regular studies while on the tour. I tell you, having to lug pounds and pounds of textbooks across Europe, and doing homework instead of sightseeing was tiresome and frustrating to say the least! Which isn’t to say that my entire off-stage time was taken up with odious school assignments: I still had plenty of time to explore the Chateau de Versaille and it’s glorious grounds (we were the first company to perform in palace theatre since the French Revolution!!) or take my camera and photograph scenic Citta di Castello just outside of Florence, Italy, for example. Touring for me is the ultimate perk of the job: having the opportunity to experience other countries and their cultures while getting paid to do what I love: to perform.

Q. When you were 18, you studied with Glenn Gilmour at the National ballet. How was the training different than what you had experienced?

Training with Jeannette Zingg at Opera Atelier’s school, I was the only boy for the majority of my training, and one of the few serious students. What a shock it was to go to the National Ballet School, be plunked into the graduating boy’s class with 9 other very serious, talented boys my own age! Not only did I discover that although the training I had received put me in good stead, these boys had been training much more intensively and I had some serious catching up to do. And to top it all off, my teacher Jeannette used the R.A.D. syllabus and Mr. Gilmour had been a Cechetti teacher, but was now teaching the Vaganova method as the National Ballet School had adopted the Russian syllabus a few years prior to my entrance.

My first class was a bit of a shock to be sure: my classmates were good dancers! But I knew that would be the case. All those hours I was sitting in Calculus or Chemistry at my regular high-school, in the back of my mind I knew that my dance contemporaries were intensively training at the National Ballet School, and I must say I resented having to finish high-school. However, once I was at the National Ballet School, I took to the new rigors immediately, and began to soak up information like a sponge soaks water. It was crucial for me to have other students my own age to see where I was as a dancer, and where I was lacking. Not that we were competitive with each other in a negative way – quite the contrary, we were always encouraging and pushed each other to achieve more – exactly what I needed to move forward.

Mr. Gilmour – I’d like to take a moment to give a little context here – is kind of the grandfather of Canadian men’s ballet in the sense that he trained the majority of the successful male dancers to come out of the National Ballet School (Canada’s largest dance school) for more than 30 years. His students have had careers spanning the globe, and many are now fine teachers themselves and have trained subsequent generations of dancers. So to have him on a daily basis, with his eye for technique and artistry, and his talent for giving concise and clear corrections, was invaluable in my training. Jeannette Zingg gave me the foundations of my training, but Mr. Gilmour gave me the final finishing that is so necessary to bridge the gap between dedicated student and professional dancer.

Q. When you joined the National Ballet you still danced with the Opera Atelier. Was it difficult transitioning back and forth in terms of style and fitting in with both companies?

I’d like to say “yes, transitioning back and forth between styles was tough” and it was, but unlike 30 years ago, today’s dancers must be able to dance in a myriad of styles, and, in fact, exposure to different styles gives a dancer a wider range of experiences which often helps them to go further in their classical technique. Maybe 30 years ago, a dancer could get a job with a company based purely on the merit of their classical technique, but today, the repertoire is so varied that without strong modern and contemporary technique, many fine classical dancers fail to make the cut. Versatility is a young dancer’s greatest asset in today’s super-competitive market.

Q. Reid Anderson, the Director of the National Ballet, left soon after you joined the National Ballet. Of the many stresses that affect the life of a dancer, I would think new directors must be one of the biggest. How did his leaving affect you?

Reid Anderson gave me my apprentice contract in 1995, and you mentioned stress: not only was I stressing about whether or not I’d be accepted into the corps de ballet, but the decision was being made by a man I’d barely met, and knew very little about. I met James Kudelka for the first time in rehearsal for his new staging of the Nutcracker which he was setting for the National Ballet that year. But meeting a choreographer in a rehearsal is very different from meeting someone in regular life: you’re in the studio to learn the choreography and be useful to the choreographer, not to get to know them as a person! Luckily for me, however, I guess James saw something in my dancing that he thought he could use, and to my great relief, I got my corps contract. By the way, if you’re ever in Toronto in the winter, definitely try to see the National Ballet perform Kudelka’s Nutcracker. It is the most interesting version of that ballet that I’ve seen, and definitely worth a watch.

Q. The new director was James Kudelka. With new directors, there must be a whole new pecking order of favorite dancers—new dancers who come, dancers who leave, new styles of classes, new types of dances to perform. How did the change affect you and the company?

As the low man on the totem pole, as it were, the change was certainly not a negative one. On the contrary, James Kudelka, as I found out later, had seen me on stage with Opera Atelier for years, and knew that above and beyond my dance technique, I had the ability to be very expressive, so I soon found myself cast in roles that required acting skill as well as technical ability. Notably, as a first year corps de ballet member, I was given the role of Uncle Nikolai in the Nutcracker (In James’ version which is set in Russia rather than the traditional Germany, Uncle Nikolai is the equivalent of Drosselmayer) a role that demands strong acting ability as well as strong technique. Unlike the usual Drosselmayer role, Uncle Nikolai in James’ version has 6 variations in the first act as he dances with all the entertainment he brings to the party, and in the finale of the second act, he has the grand pirouettes which are usually done by the Nutcracker Prince! Another high-point of my early career at the National Ballet was to be given Kolya in Sir Frederick Ashton’s stunning one act ballet A Month in the Country. The National Ballet had the honour of being the first (and I believe, to this day still, the only) company outside of the Royal Ballet to dance this masterpiece. Kolya is the role of the young boy whose tutor has a romantic affair over the summer with both the mother of the house and the daughter. Anyways, the role was created for Wayne Sleep and is technically fiendish, and also must have the right balance of boyish innocence and charm, without becoming overly saccharine.

Q. Can you point to specific points in your life when you grew as a dancer? When and what were they?

The first major turning point was getting over nerves. Up until I was 13 I was always very nervous before going on stage, and even while I was performing. But I remember a show which was the major turning point in terms of nerves: The Loves of Mars and Venus with Opera Atelier. Unlike our usual large venues with a dark and faceless audience somewhere in the void beyond the footlights, we were doing this performance as a banquet/fundraiser in a hotel ballroom where there was a small stage set up. I remember being my usual bundle of nerves until I stepped through the door and was climbing the short staircase onto the stage and I saw the faces of the audience. I realized that they were not this sombre, judgmental group of examiners set to fail me, but a crowd of interested and pleased spectators ready to have me show them what came next in the story. And suddenly I wasn’t nervous anymore, and for the first time, truly enjoyed the performance. Since then, I only get nervous if I’m extremely under-rehearsed, for example, having been thrown on at the last minute to cover someone who’s been injured.

The rest of the turning points in my career have been to do with improving or expanding my technique or expressiveness. For example, getting my first video camera, and taking it to the studio to be able to see exactly what my bad habits were, and where I needed to improve. Of course my teachers had been telling me how to improve, but it goes much faster when you can see your mistakes yourself.

Joining the National Ballet School was another big turning point, for the reasons stated above, as well as training with Goh Ballet in Vancouver.

Working with the coaches and choreographers at the National Ballet constantly helped me to gain experience and push my limits beyond what I though possible.

Beginning to work in Japan and seeing what it was like there, and doing more and different roles that I’d been given at the National helped me to grow immensely.

Working with different choreographers like Jeannette Zinngg, Robert Desrosiers, Lynn Charles, James Kudelka, Hideo Fukagawa, Robert Glumbek and Emily Molnar has also expanded my vocabulary of movement and helped shape my approach to the work.

Beginning to choreograph and to teach also helped me with my own performances because through helping other dancers to bring something more out of their dancing, I often discover that the same concepts might apply to my own roles.

Q. How do you prepare for a performance? Do you have routine for after a performance?

Of course, rehearsals are the major preparation for any performance, but if you mean on the day of the show, in general, I like to get to the theatre with enough time to be able to change into some practice clothes and lightly warm up. I try not to do a full, heavy class and tire myself out, but instead try to do just enough to make sure that my body is limber and light, and that I’m on my leg (on balance). Then if it’s available, I try to walk the stage to make sure I’m comfortable with how what I’m dancing fits on the stage, and to go over any corrections I might have received during the last rehearsal, or after a previous show. Next, I might have a small snack to make sure I have enough energy for the show, and then I go to start my make-up. Once that’s done, I get into costume, and by this time it’s probably about half an hour or twenty minutes before curtain. Next I go back to the stage to make sure that if there are any props for the show that they’re set properly and in the correct places, and finally I go back to the studio (or stay in the wings if there’s no studio in the theatre) and have another quick warm-up (a bit more stretching, or some simple small, light jumps to get my legs responsive and my heart-rate up a bit) or a bit of last minute practice with my partner, and I’m ready for the show.

After the show? Often we have to pack out of the theatre quite quickly, especially after the last show, or if we’re moving on to the next theatre in a tour, so usually as soon as I’m finished dancing, if I have spare time before the curtain call, I’ll go back to the dressing room and pack up as much as possible. Then after the curtain calls, I quickly get out of make-up, shower (if the theatre has a shower — not all do!), and either head home or to the hotel if I’m tired, or if not, maybe out for a meal or some drinks with some of the cast or friends who’ve come to see the show. When I get home, I often ice any sore or inflamed joints or tendons, and finally head to bed, sometimes to do it all again the next day.

Q. After a few years of dancing with the National ballet, you left to become a freelance dancer. What is a freelance ballet dancer? How do you get work?

A freelance dancer is one who is not tied to a particular company, but works on a short-term basis with many companies. In reality, most dancers in North America are technically freelance. Ballet companies give out contracts for a number of weeks, and have no obligation to renew for the following year. But usually once you join a major company you can expect your contract to be renewed barring a serious lapse in your performance quality or technique. Dancers working in Europe in major companies are not freelance but employees and as such enjoy much better contracts, and often paid retraining upon retirement, or even a pension.

Getting work as a freelance dancer is a question of being good enough to have companies want to hire you, usually for a specific role or piece, and being good enough at networking to get noticed.

Q. Do you need an agent? Who insures you?

Although many dancers have agents, so far, I’ve always managed to have work lined up for myself. As a freelance artist, one job often leads to more and new work.

At home in Toronto, I’m covered by OHIP, our provincial medical insurance, and when I travel, I usually purchase insurance for the duration of my trip.

Q. You dance a lot in Japan. What is that like? How is it different than dancing in Canada and Europe?

Well, for starters, rehearsals and classes are taught in Japanese! Of course the ballet terminology is still French, but all the corrections and directions, words for “upstage” or “stage left” or “lighting” or everything else pertaining to the work that’s not a direct ballet step (e.g. pas de chat, or arabesque) are all in Japanese. Another difference is that in Japan, there aren’t usually long runs of shows. Most performances are one night only, and a long run might be only 5 or 6 shows. At the National Ballet of Canada I did on average 30 performances of Nutcracker every winter! Also, being in a company full time means that you get months of daily rehearsal to prepare for a performance run, but freelancing in Japan you usually only have 10 or 12 rehearsals. But because each show is such a limited engagement, it means that in Japan it is possible to dance many different parts in a very short space of time, with different coaches and choreographers, different partners, and in different cities and theatres.

Q. When did you start choreographing? Did you have any choreographic training?

Back in 2002, I was asked to perform for a small company in Osaka, Japan, by a friend I’d met in Toronto. But I was going to be back in Canada on the performance date, so she asked if I would choreograph a piece instead. My first instinct was to decline, having had no prior choreographic experience, but then I thought that this would be the perfect chance. As opposed to doing a choreographic workshop, without the pressures of having to complete the piece for a specific performance, this was a paid job with a show at the end. So I agreed to make the piece and I found that I quite enjoyed the process.

Q. What inspires your choreography?

Inspiration can come from almost anywhere. Conceptually, it might emerge from something I have read, or a film or a play I’ve seen. Or sometimes I’m commissioned to create a specific story. Sometimes inspiration comes from a piece of music. Movement-wise, inspiration can come from improvising to the music, or maybe attempting to bridge or combine two or more styles of movement. Often inspiration comes from the facility or limitations of the dancers I’m creating on: if I’m working with students, I have to be creative within the parameters of what they can achieve, whereas with professionals, there isn’t much I could demand that they can’t deliver, so it’s up to me to decide the parameters.

Q. You also compose music. What comes first—the music or the dance? Do you compose music that you don’t use a basis for dance?

If I’m composing the music for a ballet, I’ll always start by making a rough sketch of the music. One or two of the main themes, and an approximate arrangement of those themes. Then I go into the studio and start creating movement. I always bring my computer to the studio so that if I need to rearrange the music (add or delete bars) I can do that then and there, and not waste time. Then, after each day’s session in the studio, at home, I extend or polish the music as necessary.

Yes, I’ve produced hours of music that I haven’t used for choreography. That isn’t to say that I never will, but composing is one of my main hobbies and a great way to unwind after a hard physical day in the studio.

Q. What’s the secret of your success?

Well, I’m not sure that I’m all that successful compared to some of my contemporaries… But if I had to say, it is a combination of many factors: dedication and diligence as a student, luck in finding a job, perspective to know when it was time to leave the National, more luck in finding work in Japan (thanks to my wife for helping me get started there,) the courage to try new and different things (choreography, composition, dance styles I wasn’t trained in, etc.) and most importantly, always giving whatever project I’m working on 100% of my energy and focus.

Q. What were some of the obstacles you’ve had to overcome in your career?

One of the biggest obstacles was my height. At 5′ 7”, I was always one of, if not the, shortest male dancer at the National Ballet, so naturally I got typecast in roles like jesters, Puck in Midsummer Night’s Dream, or child roles like Kolya, or other supporting characters. Many of these are demanding, rewarding, and challenging parts, and are a pleasure to dance, but they all tend to offer certain similar challenges, and not others. For example, I got very good at quick footwork, and maintaining a character while dancing very demanding solos, but almost never was I required to partner a ballerina, or to be lyrical. This was one of the major factors that led me to leave the National Ballet of Canada, because no matter how much I enjoyed the parts I got, I felt that there was a whole range of roles I had limited or no access to, and that I needed to attempt if I were to continue to grow as an artist.

Freelancing opened those doors and allowed me to work with different choreographers in a wider variety of styles, or to dance the prince and have to partner the ballerina, or to dance purely abstract parts with no set character for a change.

Q. How do you bring movement to life? As a dancer? As a choreographer?

Wow, that’s a big topic, isn’t it? No matter what the role or part is, making that choreography speak to the audience in the manner you choose is the fundamental objective when dancing. And the mechanism for achieving this communication across the footlights varies from role to role and dancer to dancer. Personally, I tend to start with the character, if there is a character, and to always try to make the steps at each moment fit with what that character must be feeling or thinking at that moment. Underlying that, whether there’s a character or not, is how I time the steps to the music. Do I want to be exactly squarely on the beat with each step, or do I want to draw certain steps out, and shade others, to create a varied accent? Which steps or poses do I want crisp and clear, and which ones do I want smooth or legato? How much energy should I put into each step? Some might require exuberance or passion, but others might require subtlety, or even lethargy or apathy. Another major factor is eye-line. It seems like a subtle detail, and it is, but whether the eyes and head are raised or lowered, or square to the audience, or shaded away from them, can entirely change the character of a moment, or even the success or failure of a step on a technical level. Interestingly, not all of these decisions need to be made in advance, though. Sometimes it’s best to leave a few options open, and to dance on instinct in the moment, in the music and in the character.

As a choreographer, the same points must be examined, and it is a choreographer’s job (over and above the actual creating of the steps themselves) to help the dancer to realize which decisions they are making, in terms of the above subtleties, are effective or not, and to help the dancer find the best balance of dynamics and emotions for each role.

Q. How important is technique in achieving artistry?

Very, and not at all. (I hate answers like that, but let me explain…) Technique is a set of tools to be used to execute a performance, to communicate with the audience. But just as a great artist can achieve amazing results with only the simplest tool, a pencil, a mediocre artist might not achieve anything at all with a full palette of paints, or state of the art digital equipment. The more accomplished someone’s technique is, the more options they have to choose from to be able to shape a performance. But this doesn’t guarantee that they will make good choices, or even understand that there is anything to shape!

Q. How do you gain the attention of the artistic director or the choreographer?

This one is simple: by dancing well. Whether in class, rehearsal, and especially in performance, a good job will gain trust from a director or get you noticed by a choreographer. Of course, it may help to be able to talk with directors or choreographers off stage. They might find your conversation interesting, and see that you have something to offer on an intellectual basis, but unless they see you dance, and dance well, they’re not going to use you.

Q. How do you promote yourself as a dancer? As a choreographer? Do you have any business training? Do you recommend dancers studying business?

As a second career, studying business, why not? But training to become a professional dancer requires too much devotion to overly diverge your energies. It’s best for dancers in training to study music, language, acting, or other things directly related to dance.

I promote myself mostly via face to face meetings and introductions from one job to the next. Sometimes I promote myself by sending an email with links to my dance clips and a copy of my bio, but unless I have a more direct link or introduction to the job, it is often a waste of time to “cold call,” as it were.

No, I have no formal business training, but becoming freelance was a bit of a crash course, at least in terms of managing schedules, booking hotels and flights, typing up resumes, preparing videos, and budgeting.

Q. How do you connect to the audience? As a dancer and as a choreographer?

Please see “How do you bring movement to life?” above. For me, the whole raison d’etre of dance is to communicate with the audience, so all the artistic and technical decisions I talk about in the above question are made with the express aim to connect with the audience across the footlights.

If you mean in the context of publicity, then I would say that I don’t have such a strong public presence as I don’t have a dedicated publicist. Of course I have been reviewed in the newspaper on several occasions, and almost always (I’m happy to say) in a positive light. And I do have clips on Youtube or Facebook with 10s of thousands of hits, and a website which gets some traffic. I hope this interview helps to get my name out there a bit 😉 Also, the students I teach are often some of the first to purchase tickets to my shows, so there’s a very real connection between those audience members and myself when I’m teaching them in a class. But I think that the best and most real connection a dancer or choreographer can make to his or her audience is by dancing on stage and reaching across the footlights, or creating that dance.

Q. What do you look for in dancers?

I suppose it entirely depends on what I’m hoping for them to be able to do. I don’t think I’ve ever met any dancer that I think I absolutely couldn’t work with. But the dancers that inspire me are dancers with a desire to dance, a technical ability to deliver the steps I’m looking for, and a personality that fits, or can adapt to fit, the character I need them to portray. I must say I’m not overly fixated with physical look, or body type. A dancer need not have ideal proportions, or incredible feet or 180 degree extensions, or be able to do 12 pirouettes as long as they can “rock the house” in the part I need them to dance.

Q. Any favorite dance books? Any favorite movies?

Books: Physics and the Art of Dance: Understanding Movement, and Physics, Dance, and the Pas De Deux,

Fonteyn and Nureyev: The Great Years

by Keith Money, and Baryshnikov at Work: Mikhail Baryshnikov Discusses His Roles

to name a few.

Movies: (dance movies) Turning Point, White Nights (!),

and Dancers,

(clearly I’m a fan of Baryshnikov) especially in White Nights. I haven’t seen Mao’s Last Dancer yet, but I’ve heard good things and am looking forward to getting a chance to see it. And I’ve heard that a movie about Fernando Bujones is in production, I hope it does that brilliant star justice! I enjoyed Robert Altman’s The Company,

even though it didn’t get such great reviews, because I thought it a rather honest portrayal of company life in contrast with many other dance films which tend to over-dramatize or over-glamorize what it’s like to be in a dance company. Center Stage

is over the top, but is fun to watch with some very nice dancing indeed.

Q. What are you working on now?

I’m in Japan right now preparing to dance in a small Gala here in Tokyo, the Arte Balleto Festival, on August 15th. I’m slated to dance the grand pas de deux from Raymonda, and I’ll also do a small suite of Baroque dances which I choreographed to music by Henry Purcell this past spring in Toronto for the celebration of the Royal Ontario Museum’s acquisition of two original Purcell manuscripts.

Q. What are your future plans?

For the short-term, I’ll continue to dance, teach, choreograph and compose as the work comes, but I probably won’t dance (and certainly not physically demanding classical ballets) for that many more years. I’d love to direct and choreograph for my own company at some point in the future, but securing funding to start a new company, or being in the right place at the right time to take over an existing company is difficult at best, so if that doesn’t pan out, I’ll continue to freelance teach, choreograph, coach, and compose.

To visit Jeremy’s website, click on the URL: http://www.jeremynasmith.ca/. To return to Ballet Connections, click on the Return Arrow in the upper left hand corner of your browser.

To see Jeremy dance, click on the the Youtube URLs below. To return to Ballet Connections, click on the Return Arrow in the upper left hand corner of your browser.

https://youtu.be/hOuF7X4hcSo

https://youtube.com/watch?v=eyzOrL46xXo%26feature%3Drelated